How NYC dancers are adapting and surviving during the pandemic?

Among the first victims of the coronavirus, New York City's dance spaces and venues went dark last March, and most dancers don't expect to return to live performance as we once knew it before Summer/Fall 2021. So how are professional dancers throughout the city surviving and navigating the crisis?

Four professional dancers share their stories of self-reinvention — re-thinking of the medium, delving into new forms, and experimenting with zoom. The goal: hanging on until the NY art scene’s revival.

Shoko Tamai is a Japanese classically trained ballerina and in 2017 she co-founded The Ninja Ballet Dance Company, a fusion between Ballet and Martial Arts.

Up until March, her company had 25 international dancers but when the pandemic hit most of them had to go back home and all her programs for 2020 cancelled, including her performance at the Dixon Place Dance Festival.

Like many artists, she turned to Zoom to teach Ballet classes from her apartment. Then in June she switched to private in-person classes. But she wanted more. “I was well aware that if I kept doing this, I had no future” Shoko says. “So, I had to force myself to think differently in order to come up with a new plan. I had to change the way my mind was programmed as a ballet dancer and understand what type of changes were happening during this pandemic in order to keep going.” She changed her perspective and then a call from the South Hamptons came in.

Several residents turned the outdoor spaces of their homes into summer stages and were looking for performing artists. Shoko was one of them and she accepted the invitation. “I felt I was back in time, when Louis XIV used to call dancers to perform at Versailles. “That’s how classical ballet started,” Shoko says laughing. The word-of-mouth worked so well that she ended up performing Upstate all summer for private clients.

These days, Shoko is creating online shows. “I know lots of dancers hate performing on Zoom and I agree,” she explains. “But while before I could only perform into one place at a time, now thanks to the magic of technology I can have one show and be at three different places. Technically, I end up having three gigs instead of one. If you use technology wisely and if you know how to adapt to the situation, you can get a lot out of it”.

Shoko’s last performance, in collaboration with painter Pedro Cuni, was streamed simultaneously in Japan, London and NYC. This dialogue between a painter and a dancer was commissioned by Hideo Sekino, a Shakuhachi player (Japanese flute made of bamboo), owner of a dance studio in Tokyo. This was a very emotional moment for Shoko, as her mother, who lives in Japan, was able to see her perform for the first time in over 10 years.

Elisa Toro is a Columbian ballet dancer who integrates Hispanic style elements (like Tango) to her performances. She is the Program Director for Accent Dance NYC, a not-for-profit organization that brings access to dance to underserved communities. “Everything stopped when the pandemic started. We had to close our programs”.

Her choreographies built around embrace were not suitable for the new situation. Forced into isolation, she took some time to rethink her approach to dance and to develop new ideas. She used her building’s rooftop to rehearse. “I have to keep creating. I want to be ready when the pandemic is over.”

Prior to the pandemic, Elisa taught an in-person class once a week. Now she has to do it on Zoom from her apartment. She teaches middle school students but “online teaching is difficult. To keep student’s attention, you have to try to be even more alive. And through a screen it is not always easy” she explains. She creates choreographies using the apartment’s space and furniture around it and encourages her students to do the same by teaching them to use the sofa as a stage prop. “You have to include it in the choreography, rely on it and a make it a part of the creation”.

While adjusting to the new situation, Elisa also had to teach herself how to use and edit videos in the most effective way. She never used this medium on her own before but had to learn because she started submitting virtual classes to a weekly dance channel on BronxNet TV. “It’s like having my own show on TV where I am the producer. It’s a solitary experience but it’s also rewarding knowing that you’ll be seen by lots of people” Elisa says.

Josh Johnson started tap dancing in High School. He grew up in Harlem playing instruments in churches with his brothers and cousins until he discovered a new way to communicate. He still considers himself a musician, but now his instruments are his tap shoes. “I make music with my feet” Josh says. “I try to resemble African Americans tap dance Masters who came before me and were so amazing at being musicians and dancers at the same time. I try to master that audio quality in a way that if you can’t see me you can definitely hear me”. Music exists in any form and for Josh it’s all about the tap dance sound. He can be in a big band on Broadway or a small jazz club, he will be the bit in the background, and tap dance will end up being the dominant force.

Before the pandemic hit, Josh taught at two different studios and performed in jazz clubs around the city. Right now, he was supposed to be in Barcelona teaching. All his contracts got cancelled. Even though he gave a few online classes, he tries to avoid Zoom. “I know that a lot of the world has changed and is transforming into this digital platform. But I don’t like it,” he admits. “I have to be physically present; I have to show up. I prefer renting a studio and have dancers come and rehearse in real life. That’s what dance is about. Getting together in a studio is where you really create.”

During the shutdown he started working out more, training in playgrounds, as he needed his body to stay strong. He also took the time to structure his ideas and figure out what to do next. “I want to be ready when the pandemic is overs,” he says

In the meantime, he keeps tap dancing and works hard to strengthen his weaknesses as a dancer. Although far away from his Brooklyn apartment, he regularly travels to Harlem’s Marcus Garvey Park where he practices on the outdoor stage. “This is a special place to me,” he says “This is where it all started for me. When I first learned to tap dance, I used to go there to practice. I feel at peace on that stage. And this is also the place where other tap dance Masters went, way before me.”

While the pandemic forced the cancellation of his plans for the near future, it didn’t impact his drive to continue dancing. “Everything can be gone and stopped I would still be dancing. I am a strong-minded person and motivated regardless of the circumstances.”

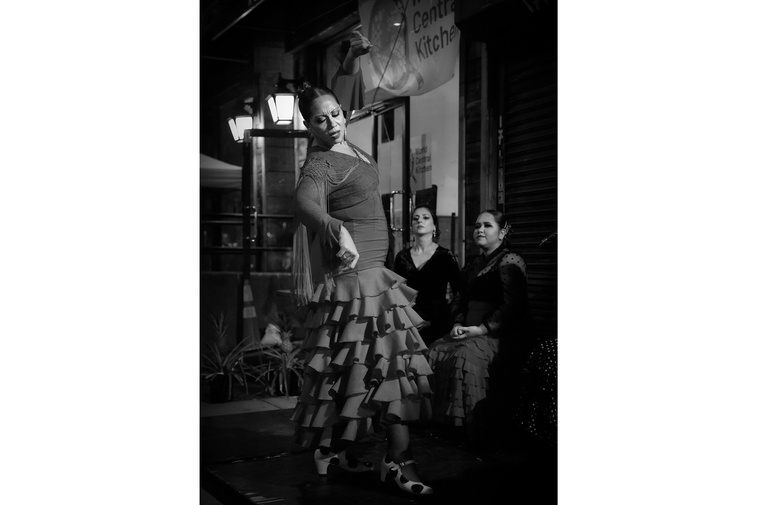

Xianix Barrera, founder of The Xianix Barrera Flamenco Company, has spent the last 16 years mastering the art of Flamenco. “When the pandemic arrived, it was a panic moment, she said. “The NY Flamenco Festival had just been launched with a flash mob dance and then that was it. It happened fast. In two or three days, people were cancelling, and thousands of dollars were gone” she added. All of her shows and plans for the months to come were called off. It took her a few days to process the situation and figure out how to keep going.

Within a week she moved her flamenco classes online. But despite a large investment in sound, video and lighting equipment, she didn’t find the weekly Zoom classes hosted from her apartment fulfilling. She also lost some of her students to cheaper virtual classes hosted by teachers living in Spain.

Today, Xianix is back to teaching. She uses NYC parks’ spaces for kids’ classes while adults’ ones could resume in her studio in El Barrio’s Artspace (formerly PS 109) where she also lives.

Social distancing doesn’t allow for more than four indoor students, so she mixes her class with Zoom sessions, although as she points out Zoom is not made for dancing, “especially flamenco.” “You have the sound of your feet, the sound of your voice, the sound of your hands and the music. Four competing sounds that you try to get into the system and project to the students. The internet comes in and out, the screen freezes, the sound is delayed. The video and the sound don’t always sync. All this doesn’t make it easy”.

Xianix struggles with the uncertainty of her new life and worries she might never go back on stage, even more so now that winter might put a stop to her outdoor weekly gigs at a few NYC restaurants.

"This summer I experienced a burnout. I was about to quit a few times, thinking I didn't want to dance anymore.”